In January 1975, the same year and month when Keith Jarrett performed in Cologne recording the world’s most famous “solo piano” jazz album (The Köln Concert), on an equally influential Italian music front, the “canone italiano,” Rimmel was released.

The fourth studio album by Francesco De Gregori, which stayed on the charts for 60 weeks and sold half a million copies.

De Gregori and the “fragment of light”

There has been much written about the semantic subversion that the Roman singer-songwriter has imparted to the song form, his skillful verse weaving, as well as the difference between poetry and song. On this matter, poet and writer Alessandro Rivali, speaking to Tempi, offers a wisely definitive viewpoint: “For a lifetime, De Gregori, humbly, has shielded himself from the word poet. He may not be one in a technical sense, of course, but like Manzoni or Melville, if someone is capable of so marvelously illuminating the mystery of life, then poet he is, in fact.”

But there’s more. “The fascinating thing about the album Rimmel,” Rivali emphasizes, “is the chain of images that follow one another, often far from sequential, but it is exactly in this that their beauty lies. I grew up with Ezra Pound, a poet I believe is very distant from Francesco De Gregori, but in his Cantos, the poet theorized precisely the ‘fragment of light,’ that is, the proceeding with luminous splinters that the reader must then piece together and interpret.”

“The jaw from the courtyard spoke” (or of a pacifist anti-fascism)

The fact that the total twenty-nine minutes of Rimmel – an anthem to brevity – only hint, suggest without concluding, is a fact. Just as it is equally true that the nine songs on the album all refer, in a fascinating interweaving, to De Gregori’s personal story and that of all Italy. Le storie di ieri, for example – a song released a month apart on both Rimmel and Volume 8 by De Andrè – is perhaps the most political and openly autobiographical song on the album, always in the sign of that mix of personal and public history that characterizes the storytelling of the singer-songwriter.

For the director of Edizioni Ares, “Le storie di ieri is almost a manifesto of the 20th century, a reading of all the drama of the Italian 20th century, of the rifts that characterized it and above all of the unnecessary deaths. In this sense, ‘I cavalli a Salò sono morti di noia / a giocare col nero perdi sempre’ is a very concrete verse. But it is also true that looking at the work and the degregorian biography as a whole, behind it we must also read the painful story of his uncle, commander of the Osoppo brigade, slaughtered in Porzûs by the communist partisans.”

The song begins with a synecdoche on Mussolini (“the jaw from the courtyard spoke”); it then goes on to express distrust about the emerging Social Movement and Almirante (“And today there is still a black writing / on the wall in front of my house / saying that the movement will win / the great leader has a serene face, the tie matching the shirt”); and it ends with the relationship between a very young De Gregori and his father, who grew up during fascism to the extent that he has “a shared history / shared with his generation.” Giorgio De Gregori, a librarian who rose to the top of the Aib (the Association of Italian Libraries), is described as a “quiet boy” who “reads many newspapers in the morning,” who “is convinced of having ideas” but who has a son with a different point of view. Hence “a pirate ship.”

“Dad, don’t worry, you’re not involved”

A political distancing, certainly, but whispered, discreet, even tinged with some guilt. About the “family lexicon” contained in Le storie di ieri, he told music journalist Paolo Vites:

“When my father heard it, he said, ‘But what do I have to do with it?’ And I said, ‘Dad, don’t worry, you’re not involved.’ To show you how in a song autobiography is important up to a certain point. Not always when one says ‘my father’ does he refer to the biological father. It still saddened mine a bit, also because the song […] was heard by many and there were people who […] told him, ‘Giorgio, I didn’t know you were so right-wing.’ In the end, I was also sorry to have mentioned him, or to have created this misunderstanding.”

“De Gregori has the measure of grace”

The description of a non-muscular anti-fascism, without Greek tragedies and Neapolitan melodramas (with a reference to certain “unbearable” acting performances) says a lot about the “measure” with which the singer-songwriter has always operated.

“De Gregori has the measure of grace,” Rivali concludes, “his is a poetics of kindness, of the poised but at the same time profound way of expressing things. That’s why in his case, I speak of elegy, because his songs have a particular delicacy, capable of touching the heart like the best poetry. The mildness as an expressive form must be matched with his dreamy vein, typical of poets. It would be interesting to conduct a study on the recurrence, in his songs, of the word ‘dream.’ Even in the mentioned song, Le storie di ieri, the child ‘closes his eyes and starts to dream.’ In Buonanotte fiorellino, De Gregori notes that ‘to dream of you, I have to have you close / and close is not close enough’.”

“Santa voglia di vivere e dolce venere di Rimmel” (a verse without tricks)

Autobiography yes, but always sublimated.

Exploring the Poetry of Francesco De Gregori’s Album “Rimmel”

As Malcom Pagani wrote in Il Foglio, “whether he wore a baseball cap or a wide-brimmed hat, Francesco found shade. Sheltered from definitions. Shields up was a necessity. Hiding a duty.” After a slightly country piano intro, the title track of the album (never the same in live performances because “if every time I perform Rimmel I had to restore a tabernacle… it would be an ideological falsehood”) begins with a jarring conjunction. This, in turn, drags along the end of a love story: “And something remains / between the clear pages and the dark pages.” Then, after playing cards, gypsies, alibis, tricks, fur collars, and other cinematic images, everything culminates in a photo she asks him for, the one “where you were smiling and not looking.” And when the twenty-three-year-old De Gregori replies “without understanding,” he is told that that photo “is all you have of me.” And unfortunately, “it’s all I have of you.” Rimmel speaks of a love dwindling in a resigned, fatalistic, minimalist manner, therefore absurd and heart-wrenching.

“Lines like ‘Now you can send your lips to a new address / and overlay my face with someone else’s’,” explains Alessandro Rivali, “don’t need philologists to show their immediacy.” For the Genoese writer, “the song also contains ‘molto’ verses, which have a beauty that is totally and properly literary. I think of ‘Holy desire to live / and sweet Venus of Rimmel,’ which beyond the alliterative ‘v’ play, is a verse from a true poet that could easily inhabit a songbook of the 20th century.”

Pieces of Glass, the “Rosicata” that Becomes a Masterpiece

Another veiled autobiography is found in the most loved song by fans of the singer-songwriter, Pieces of Glass. A song as cryptic, allusive, and, for Fossati, “poetically dizzying” as it is banally ordinary in its genesis. In an interview with Corriere in 2015, reported in the colossal philological work of Enrico Deregibus (Francesco De Gregori. The Lyrics. The Story of the Songs, Giunti), the singer-poet spoke thus:

“I was walking in Piazza Navona with my girlfriend at the time. Among the many street artists, there was one who ate fire and walked barefoot on broken glass. At one point, my girlfriend said, ‘But, how handsome that guy is.’ And that’s where the story ends, it was just a moment of light jealousy. From there, the incipit of an autobiographical song was born.”

The story of what, in general terms, De Gregori describes as a “rosicata” sparked a flurry of interpretations and exegesis that has lasted for fifty years. The point of view is that of a third party watching a woman fall in love with a freely anarchic Italian emigrant, who, while playing with his existence and his pain, is anything but a sideshow phenomenon (“nothing to do with the circus / neither acrobat nor fire-eater”). He is rather a brash artist, a “saint barefoot” who “jumps and wins on glass,” who “breaks bottles and laughs,” because he knows that “hurting oneself is not possible / dying even less so.” He is a symbol of vitality whose irresistible charm is all played out in his uncommon experiential dynamics: he is completely master of his existence (“He seriously replies ‘It’s mine!’ / implies life”). And at his last attempt to impress (“When he says, ‘It’s been four days since I love you!'”), the girl, in a finale of rare intensity, can only surrender: “And you still don’t understand why / you left everything you had in a minute / but you’re happy where you are.”

“An Elegy of Absence. Reminiscent of Montale’s Le occasioni“

As an established (and award-winning) poet, Alessandro Rivali argues all this with enlightened knowledge. “Pieces of Glass,” he confides in Tempi, “like the entire album it is part of, is nothing but an elegy of absence. An author always writes for something missing, whether it’s a lost Eden, a finished love, a deceased father… In this sense, the songs of Rimmel remind me a lot of Le occasioni by Montale, a songbook entirely built on absence.”

He adds: “We know that De Gregori is a great reader of American literature, he adores Cormac McCarthy, but we don’t know what relationship he has with Montale. However, he loves Dino Campana, to whom he dedicated a song, and like him, he is poetically mysterious, somehow reticent. Gianpiero Neri, my master in poetry, said that Campana is a point of no return of the 20th century; that many verses of De Gregori have a dreamlike derivation, typical of Dino Campana and his Canti Orfici, is something significant.”

Pablo is a “Colleague,” Not a “Companion”

Aside from the shielded self, an album released in the mid-1970s cannot help but contain echoes of class consciousness. In Pablo, a hypnotic song, the narrator is a poor and orphaned Italian emigrant (“My father buried a year ago / no one else cultivates the vine”). His friendship with a “Spanish colleague” inclined to betray his wife “with women, wine, and green Switzerland” will end in the worst way possible: in a work accident, Pablo will end his precarious life in every sense by falling from scaffolding. From there, the “chorus” of the other workers: “They killed Pablo and Pablo is alive.”

La genesi di un cantautore: Francesco De Gregori e la scelta delle parole

La musica di Francesco De Gregori è un universo complesso e affascinante, dove ogni parola ha un significato profondo e un impatto emotivo. Ma è nella scelta della parola “collega” che va indagata la genesi di quell’atteggiamento sfrontatamente apolitico che De Gregori, malgrado tutte le etichette subite, si è da tempo scrollato di dosso. Era l’anno 2000, e a Maria Lombardo, scrittrice e critica cinematografica, il cantautore romano rilasciava queste parole:

«La parola “compagno” […], per quanto allora andasse di moda, era ingombrante dentro quella canzone. L’avrebbe trasferita immediatamente nell’ambito delle canzoni di lotta […]. Perciò in Pablo si parla di collega spagnolo e non di compagno spagnolo. Ci ho ripensato a distanza di tempo e mi sono chiesto perché mi dava fastidio la parola “compagno”. È forse perché la canzone in questione vuole tratteggiare la figura di un signore che muore in quel modo, al di là delle ideologie. È un Malavoglia, Pablo, non ha né coscienza sociale né politica. È una vittima dell’ingiustizia del mondo, non è vittima di una controparte politica. Forse questo c’è in molte mie canzoni che riguardano “il sociale”, come si direbbe oggi. E forse questo ha generato anche, a suo tempo, incomprensioni e accuse di ambiguità. Quelle di cui parlo sono vittime del mondo».

De Gregori è Rimmel & Nobel

Nei tributi che in queste settimane la stampa ha dedicato a Rimmel, come un orologio svizzero è sempre tornata puntuale la vecchia e strabordante stroncatura di Giaime Pintor (De Gregori non è Nobel, è Rimmel), nella quale il figlio del fondatore del quotidiano Il manifesto rinfacciava al cantautore, tra molti affondi, «la presunzione di far poesia», un «canto degregoriano kitsch» e una zuccherosità da «baci Perugina». A distanza di 50 anni l’abbaglio è evidente. «Pintor bollò come sdolcinato ciò che non lo è affatto», così il direttore di Edizioni Ares. Che a Tempi precisa: «Un autore è grande quando riesce a trasmettere l’universale attraverso i dettagli. Un verso come “Ora un raggio di sole si è fermato / proprio sopra il mio biglietto scaduto” avvicina De Gregori a Raymond Carver, scrittore che partendo dall’ordinario, dal quotidiano, costruiva splendide epifanie».

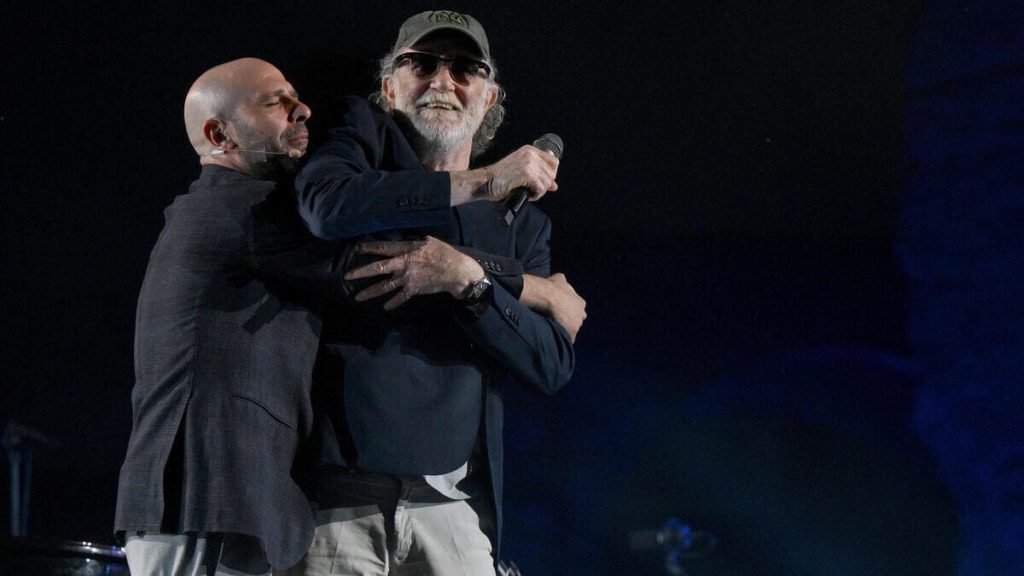

Il 31 ottobre, da Bologna, partirà il “Rimmel Tour”, prima nei teatri, poi nei Palasport di Roma e Milano e infine nei club. Ventisette date a loro modo “indispensabili” per vivificare memoria collettiva e santa mendicanza di un’Italia che «non sa dove andare / comunque ci va».

Leggi anche