The Impact of Lower Speed Limits on Air Quality and Health

Is driving slower in a car affecting air quality and damaging our health? This seems to be the conclusion of a study by the MIT Senseable City Lab that attempts to estimate the effects of implementing a 30 km/h speed limit in the city of Milan. The analysis has garnered significant attention and surprise – the Corriere even described it as an “incredible study.” However, when looking closely at the numbers, much of the buzz may be unwarranted, or almost. Let’s take a closer look.

The Effects of a 30 km/h Speed Limit on Air Quality

There are many factors that determine the amount of pollutants emitted: the number of cars on the road, the distances traveled, the speed at which they move, and the types of vehicles.

Now, it’s not news that the amount of exhaust gas produced by a vehicle traveling at a constant speed of 50-60 km/h is much lower than that of a vehicle traveling at 20 km/h. The emissions curve resembles a “U-shape”: starting from high values, it decreases to a minimum and then rises again for higher speeds. Travel in cities is usually done at an average speed lower than the optimal speed, so measures aimed at reducing it have a partially negative effect offset by the reduction in acceleration phases. However, this is just the first effect.

Enforcing, and ensuring compliance with, lower speed limits leads to an increase in transportation costs – time is money – and therefore reduces travel in the area affected by the measure. And the picture is not complete yet: policies aimed at locally combating car use can result in a different distribution of trips in the area – fewer trips in the city center and more in the suburbs.

Today, Cars Pollute Less

The above aspects should be viewed in a broader context where the dominant factor in improving air quality is the renewal of the vehicle fleet. Thanks to technological innovation, starting from the seventies for some substances and then for all major pollutants from the nineties with the adoption of catalytic converters and particulate filters, the gases and dust produced by road vehicles per kilometer traveled have been drastically reduced. One Euro 0 vehicle used to pollute roughly as much as twenty Euro 6 vehicles. Thanks to this progress and similar ones in other sectors, the sky in our cities has become increasingly blue despite the increase in traffic.

This trend is expected to continue in the coming years, thanks to the increasing number of electric vehicles on the road. All mobility policies are destined to have an increasingly marginal impact. The 2.7% increase in particulate emissions estimated by the MIT Senseable City Lab is nothing more than background noise, essentially imperceptible with air quality measurements, especially because in Milan, vehicular traffic contributes to this pollutant in the air for a modest share, around 15%.

Considering Safety and Travel Times

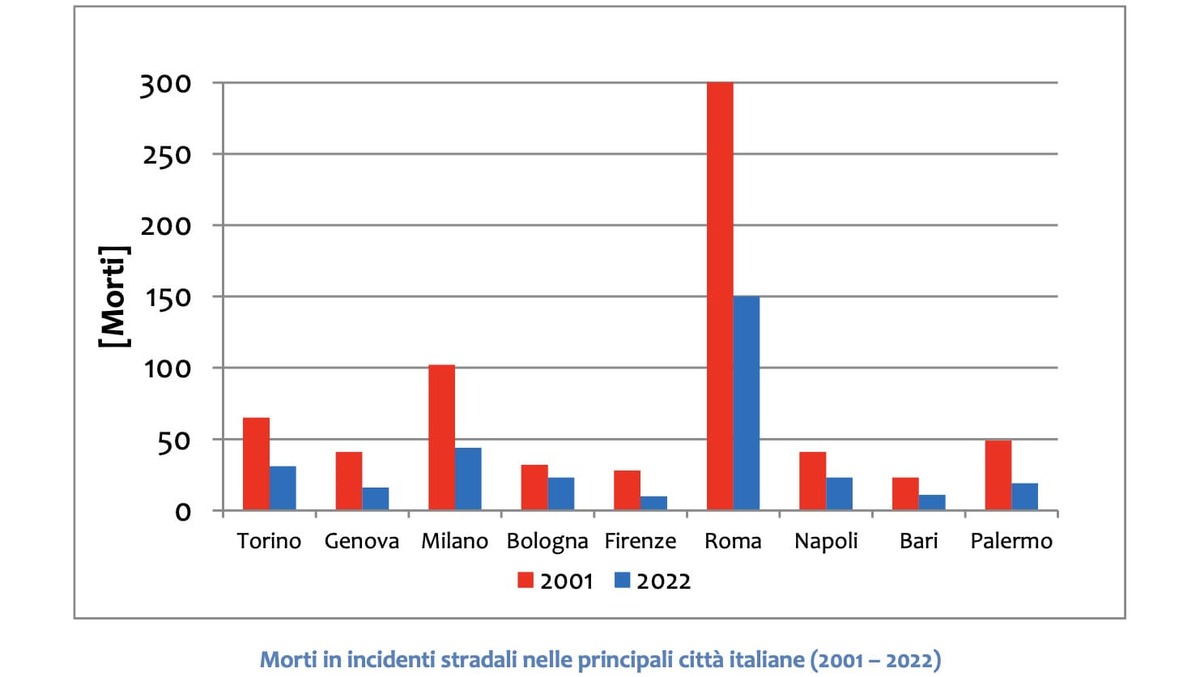

In a serious evaluation of measures to reduce the maximum speed, safety and travel times should be considered. Driving slower reduces the severity of accidents. But even in terms of safety, it should not be forgotten that the trend over decades has been very positive: for example, in the eight largest Italian cities, the number of road casualties decreased from 687 in 2001 to 327 in 2022.

A cost-benefit analysis of the “city at 30 km/h” in Bologna, while not providing an estimate of the expected reduction in casualties as it would be “values too low to obtain reliable estimates,” provides a positive assessment of the measure: the positive effect of reducing the number of injuries and accidents more than outweighs the cost resulting from longer travel times. The document also correctly notes that “the benefits, largely determined by the reduction in accidents, could be scaled down in an optimistic scenario of a generalized reduction in the phenomenon resulting from other concurrent control policies as well as the technological evolution of vehicles.”

The Bike as an Alternative to Cars Is Not the Solution

Therefore, the advantages and disadvantages should be carefully weighed before intervening, and the results should be monitored. Unless a war on cars without ifs or buts is desired, it is necessary to carefully tailor the approach by looking at cases of great success and not acting indiscriminately. For example, in Oslo, the number of casualties has been almost zero while maintaining a speed limit of 50 km/h or higher on all non-secondary roads.

And if the overall safety of road transport is truly important, promoting cycling as a replacement for cars should not be encouraged. Increased use of bicycles seems to be in conflict with reducing mortality. In the case of the Netherlands, for instance, while the number of casualties among car users decreased from 609 to 205 between 1996 and 2022, the number of cyclist casualties has been increasing in the last decade, reaching 291 in 2022 (141 of which were caused by collisions with cars), the highest value in the analyzed period.

Relative to the population, it is as if there were a thousand cyclist casualties in Italy compared to the 185 actually registered, despite a much higher mortality rate and significantly lower bicycle usage. This outcome does not seem desirable.